An Artist's Odyssey

William E. Reaves

William E. Reaves is a retired educator and, with Linda J. Reaves, general editor of the Joe and Betty Moore Texas Art Series at Texas A&M University Press. He is the author of Texas Art and a Wildcatter’s Dream: Edgar B. Davis and the San Antonio Art League (1998), coauthor with Andrew Sansom of Of Texas Rivers and Texas Art (2017), and coeditor with Bob Kinnan and Linda J. Reaves of King Ranch: A Legacy in Art (2021).

On February 3, 1984, Texans awoke to news of the passing of Buck Schiwetz. One by one, accounts of his death rolled across the state and onto the pages of Texas newspapers large and small. In the weeks immediately following the painter’s death and his subsequent interment at the State Cemetery in Austin, dozens of Texas newspapers carried announcements, accompanied by out-of-state news accounts in more distant outposts such as Albuquerque, New Mexico; Alexandria, Louisiana; Atlanta, Georgia; Muncie, Indiana; and New York City. Schiwetz’s life and achievements were memorialized by fine arts and literary columnists in Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio, and his contributions were the subject of editorials on the pages of the Houston Post and the San Antonio Express. The breadth of this news coverage was atypical for a Texas artist of his period (as it would also be today), yet the newsworthiness of Schiwetz’s passing and the scale of coverage imparting his loss merely reflected the notoriety and popularity that he had garnered over a lifetime of work in Texas.

Even before his passing, Buck Schiwetz had often been referenced as the state’s best-known artist, and he was likely just that. Texans in all corners of the state were well acquainted with his trademark renderings of iconic Texas landmarks and drawings of indigenous architecture that had so often adorned pages of the popular media. Many had embraced the artist through his best-selling art books, which illuminated the legacies of his home state, and many others had admired and collected original Schiwetz paintings and drawings that had hung in Texas museums and galleries over a sixty-year span.

Less than a year before his death, Schiwetz had been feted by Art League Houston as the organization’s inaugural “Texas Artist of the Year” at a grand gala co-hosted by Texas governor Bill Clements (1917–2011) and Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby (b. 1932). The affair, a signal honor for the aging artist-laureate, was held at the city’s storied Shamrock Hilton and attracted a crowd of over five hundred admirers.1 The two-volume set of written testimonials that survive the event reads like a who’s who of the elites of Texas arts, letters, commerce, and politics of the day.2 For Schiwetz, a humble man long-accustomed to plaudits, the Houston gala marked the second time that he had received acknowledgment as the state’s premier artist, having previously received similar honors as “Texas Artist of the Year” from the Texas legislature some six years earlier.

These recognitions were merely accoutrements to the already impressive list of Texas bona fides that Schiwetz enjoyed at the time, including his designation as a Knight of San Jacinto by the Sons of the Republic of Texas, his prestigious appointment as a Fellow in the Texas State Historical Association, as well as distinguished memberships in the Texas Philosophical Society and the Texas Institute of Letters. Indeed, Schiwetz’s influence on the Texas scene had grown so pronounced over the years that, as early as 1965, San Antonio writer Gerald Ashford made the argument that Schiwetz was the only man in the state who could rightfully assume the mantel of “Mr. Texas” following the deaths of Frank Dobie (1888–1964), Walter Prescott Webb (1888–1963), and Roy Bedichek (1878–1959), all icons of Texas literary society and all close comrades of the artist.3 Based on his life’s work as an artist, illustrator, and preservationist, Buck Schiwetz had earned the affections of his fellow Texans. He had been heralded as an authentic troubadour of Texas arts and letters and held sway near the end of his life as a favorite son within his native state. Thus both his presence and his passing were of substantial note across the vast contours of Texas.

It has been posited that imagery of E. M. Schiwetz has appeared in more publications than that of any other Texas artist or illustrator. Indeed, the artist’s visual interpretations of Texas, along with his annotated observations, had been the subject of four books published during his lifetime. These volumes were highly acclaimed and were accompanied by essays penned by important Texas authors and historians—Walter Prescott Webb, Leon Hale (1921–2021), Eddie Weems (b. 1924), and R. Henderson Shuffler (1908–75). These Texas authors, just as Dobie and Bedichek, were unabashed members of the Schiwetz fan club, and because of their close relationship with their protagonist, their writings tended toward more personal anecdotes of the artist’s life and persona. Taken together, their essays flesh out an endearing portrait of the man who was Buck Schiwetz and comprise a collection of oft-told Schiwetz tales. Their stories tell of youthful shenanigans of a rural childhood; rocky, yet triumphant, college transitions into architecture; adventuresome train-jumping episodes in pursuit of an innate Texas wanderlust; and even quirky quests to crack the art centers of New York. Certainly, there are accounts of his life and times as a successful Texas “ad-man,” and, in some instances, the authors even relate the artist’s stories of personal tragedy and loss.

Despite these lyrical accounts, however, the written word on Schiwetz to date leaves his portrait unfinished. For as entertaining as these assembled reflections and anecdotes may be, they reveal little of Schiwetz’s accomplished career as a fine artist, and they fail to trace his full influence in fields of Texas arts, letters, and cultural preservation. Here we seek to add depth and measure to the extant Schiwetz story, addressing lesser-known accomplishments of his professional career and documenting more deeply his rise as a successful artist and illustrator. Also offered for the first time is a retrospective examination of the artist’s full body of work through the eyes of two contemporary art scholars and an architectural preservationist—Kelly Montana, Sarah Beth Wilson, and David Woodcock, respectively.

Born to Draw

Edward Muegge Schiwetz was born on August 24, 1898, in the South Texas hamlet of Cuero. He was the oldest of five children born to Berthold and Anna (Reiffert) Schiwetz (1866–1939 and 1876–1952, respectively). Early on, the young Edward was assigned the moniker of “Buckshot” (later shortened to “Buck”) by the mayor of Cuero, a relative on his mother’s side. The nickname seemed to stick.

Buck’s father, Berthold, was a third-generation descendent of the German families who had immigrated to Texas in the late 1840s through the fabled port city of Indianola. Moving inland through Victoria, the family eventually settled in the Meyersville area, close to Cuero. Berthold Schiwetz became a successful banker and merchant in Cuero. Conservative and traditional in his German patriarchy, he was prominent in the affairs of the town and its surrounding areas, serving as president of Cuero’s school board as well as a director of the nearby Spoetzel Brewery in Shiner.4

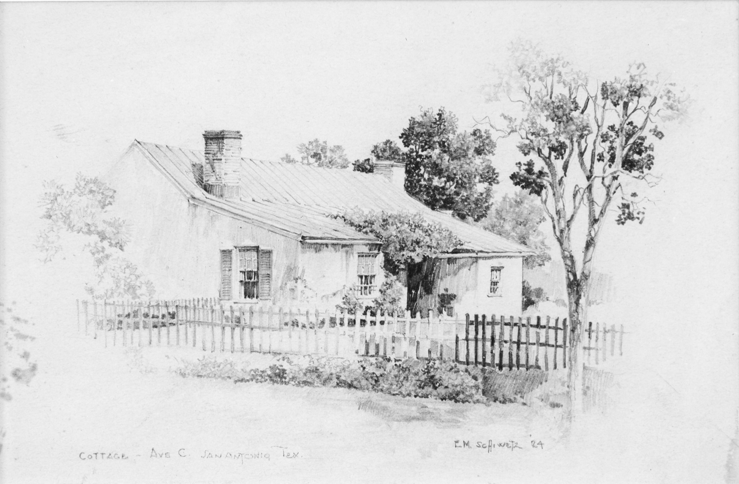

Buck’s mother, Anna Schiwetz, raised her five children in a structured, well-disciplined home. Artistically talented in her own right and with early arts training in San Antonio under José Arpa (1858–1952), Anna nurtured the artful inclinations of her children from a young age. Upon discovering his mother’s student sketchbooks in the family’s attic, Buck was enthralled, increasingly interested in applying his own hand at drawing and sketching. He was encouraged by his mother to perfect his apparent skills in this regard. Anna ensured that the budding young artist maintained ample supplies of paper and pencils as well as a space for his production. Later, as the youngster’s interests and skills progressed, Anna enrolled him in private lessons offered by Mary Louise Gramann, a local china painter and teacher in Cuero.5 Buck maintained a persistent interest in drawing throughout his school years, often to be found sketching local subject matter in Cuero and, later along with his close friend and classmate Thomas Stell (1898–1981), churning out innumerable automobile designs in their shared fascination with the emerging automotive industry.6 For both young men, their creations foretold eventual prowess as professional artists, their automotive visions presaging the industry’s later trend of sleek new design.

Through his high school years, Buck was still avidly sketching and serving as the art director of the Cuero Gobbler, the school’s annual. He contemplated art school in Chicago as a postsecondary option and made his preference known to family but found himself overruled by his father’s more pragmatic, career-centered vision for his son’s future. Rather than art school, Berthold Schiwetz insisted that his eldest son attend Texas A&M College and study electrical engineering, certain that the emergent new field would be the more lucrative and prosperous course of education. Buck demurred to his father’s wishes, but in a story now well-known, his college pursuits of electrical engineering were halfhearted at best and almost proved to be an academic disaster for the young “scholar” from Cuero.

At Texas A&M, Schiwetz’s grades in engineering were soon “underwater” with academic deficits so severe that he was at serious risk of dismissal. Faced with the prospects of expulsion, Schiwetz was saved by the benevolent intervention of the president of A&M College. In a phone call to Buck’s father, President W. B. Bizzell brokered a compromise with the familial patriarch, through which Buck was allowed to enroll in the architecture program. For his part, Schiwetz did go on to complete the undergraduate regimen in architecture and earn his bachelor of science degree in the field. He continued to ply his sketching skills as an artist for the Aggie yearbook, the Longhorn, eventually rising to the role of art director. He even extended his architectural studies at A&M beyond undergraduate requirements, maintaining his status as art director for the Longhorn while a graduate student.7 While he maintained an acceptable record in his graduate classes, he apparently excelled in his role as art director at the Longhorn. In 1922, the Cuero Daily Record carried a story headlined “E. M. Schiwetz Doing Great Work at A&M Says Instructor.” The paper reported the observations of S. C. Evans, head of A&M’s Boys Work Department on his visit to the town:

Cuero is quite on the map at College Station, and it has been put there by Edward Schiwetz. His artwork, particularly that done in The Longhorn last year has attracted the attention of a number of lithographic companies back East, as well as Texas concerns. Those in a position to know this young man’s work during the four years at the College predict a brilliant future for him. Last year he had a number of cartoons accepted by the college number of Judge. When he finishes his four-year course in architecture this spring, he plans to take up commercial art for a while at least.8

It is not recorded how this local testimonial may have been received by Schiwetz’s father, but perhaps it was with some modicum of relief. Nonetheless, over the course of the 1921–22 session at Texas A&M College, Buck did complete his course in architecture as projected by Professor Evans, going further to complete all but a few of the graduate courses necessary for a master of arts degree as well. He departed College Station by the end of the 1922 term with the intent of pursuing his stated objective of work in commercial art, for a while at least.

Schiwetz returned home to Cuero from Texas A&M in late spring, apparently awaiting prospective offers from architectural or advertising firms that had purportedly courted his candidacy during his work on the school’s annual. Unbeknownst to Buck, however, his departure from Texas A&M had proven untimely for the new graduate, and the employment offers that the young Schiwetz had anticipated failed to materialize.

While Buck was completing his professional studies at A&M, the state’s economy had settled into the recession of 1921, which continued into 1922. Webb referred to this period as “the panic of 1921, when all the cowmen and farmers went broke in post-war deflation.”9 The slowing economy restricted the job prospects that Buck had counted on for his professional debut. His weeks back home in Cuero awaiting job overtures stretched into months; even viable hometown options seemed illusive. During his wait, Buck continued to sketch at every chance and exercised his penchant for Texas travel, thumbing rides to San Antonio and Austin. He even embarked on an extended canoe journey down the Guadalupe River with a high school friend, foreshadowing in his sketches the same sort of epic Texas river journey later so eloquently recorded in prose by his author-friend John Graves (1920–2013).10

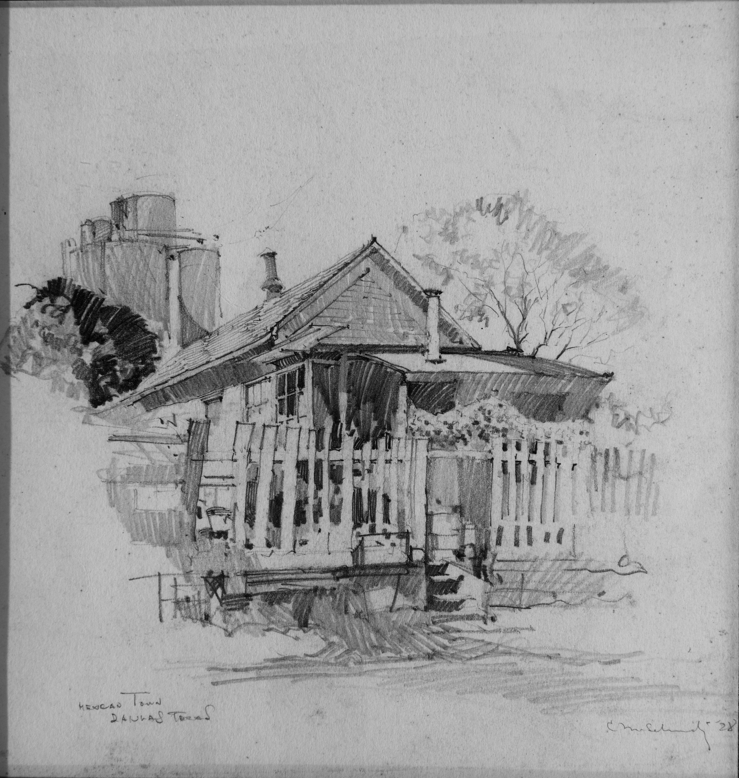

As the days wore on with no offers in sight, Schiwetz’s exasperated father issued a new edict to his son, directing him to move immediately to Dallas and seriously engage in pursuit of job prospects there. Berthold underwrote Buck’s train fare and staked his young son with adequate pocket change for the trip but apparently offered little else. And with that, twenty-four-year-old Buck Schiwetz departed Cuero for Dallas in the early fall of 1922, thrown essentially into the “deep end” there by his father to sink or swim on his own. In Dallas, the talented young novice struggled and flailed about in efforts to stay afloat and to eventually forge his path toward a livelihood in art. Over what would become an eventful four-and-a-half-year stint in the city, Schiwetz would indeed begin to fulfill the promise that his A&M instructor had predicted for him back in Cuero. Hustling to find his way, the young artist somehow managed to find meaningful work, continue his own professional development as an artist, and perfect his skills as an architectural delineator.

The Search for a Place in Art

In his quest for gainful employment, Schiwetz called on numerous commercial art enterprises and architectural firms in Dallas, eventually coming to the attention of John Doctoroff (1893–1970), a well-established commercial artist and portraitist with formal training at Cooper Union in New York. He had maintained a studio in Dallas since 1918, and by the time Schiwetz approached him, Doctoroff was well-known and active in Dallas professional, social, and business circles.11 In lieu of employment, Doctoroff consented to “apprentice” the recent graduate. His proposition offered Schiwetz a role as understudy, with access to a modest workspace along with observation and critique by the more experienced artist but with no exchange of money so vitally needed by a starving young upstart. Nevertheless, Schiwetz welcomed this apprenticeship as his entrée into the world of commercial art, affording him his first professional (albeit informal) affiliation with an established commercial art firm, as well as a chance to learn the trade and perfect his craft under watchful observation of an experienced principal. Subsisting on odd jobs and occasional outside assignments, Schiwetz capitalized on his time with Doctoroff to achieve a professional foothold in the city. He began to build a network of business contacts in the field and utilized his association as a base through which to gain insights into the Dallas commercial art scene. Schiwetz’s exact tenure with Doctoroff is unknown, but he likely worked with him for only about six to eight months, as records show that John Doctoroff left Dallas near the middle of 1923 to return to Chicago, where he advanced his own art training through attendance at the Art Institute of Chicago and completed his career as a successful portraitist there, attaining notable sitters such as Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Wendell Wilke, and John J. Pershing.12

Following his apprenticeship with Doctoroff, Schiwetz seems to have progressed to salaried assignments—although meager salaries at first. Briefly he served as an assistant to Dallas theater designer and architect Scott Dunn (1887–1937), a former instructor at Texas A&M College.13 In early 1924 he took employment as a draftsman in the offices of Guy F. Cahoon (1889–1944), another important Dallas commercial artist with a strong array of clients. He had opened the city’s first commercial studio in 1914, eventually becoming well-known for scenes of Dallas in charcoal, watercolor, and etching. He became a mainstay in commercial and architectural communities and was active in the emergent fine arts scene in Dallas. In 1936, Cahoon was designated the official artist for the Texas Centennial and the State Fair of Texas.14

Schiwetz recounted that Cahoon paid him a salary of one hundred dollars per month during his time with the firm. Despite such sparse compensation, Schiwetz reported that he learned valuable lessons from Cahoon regarding financial aspects of the business as well as furthered his techniques in architectural drafting under the senior artist’s expert tutelage. Cahoon’s assignments also presented Schiwetz with his first exposure to the press of constant deadlines that characterize commercial work. Schiwetz complained of the stressful nature of his work with Cahoon, chafing at the pressures of far too many assignments imposed with far too little time. Even more alarming to the young associate, however, was that Cahoon would often present Schiwetz’s completed renderings to clients replete with his own signature instead of that of Schiwetz.15

Schiwetz took leave of Cahoon’s employ some time in late 1924 and soon relocated to the Dallas architectural firm of Thomson and Swaine. The firm had already established a reputation as the city’s premier residential architects at the time, serving as architects for developers of exclusive garden communities such as Highland Park in Dallas and River Oaks in Houston.16 Ensconced in the firm’s “country club” set, Schiwetz gained recognition for his skill in architectural rendering or delineation, an important professional role in architectural firms at the time. His work as an architectural delineator provided him broad exposure and contacts in both Dallas and Houston.

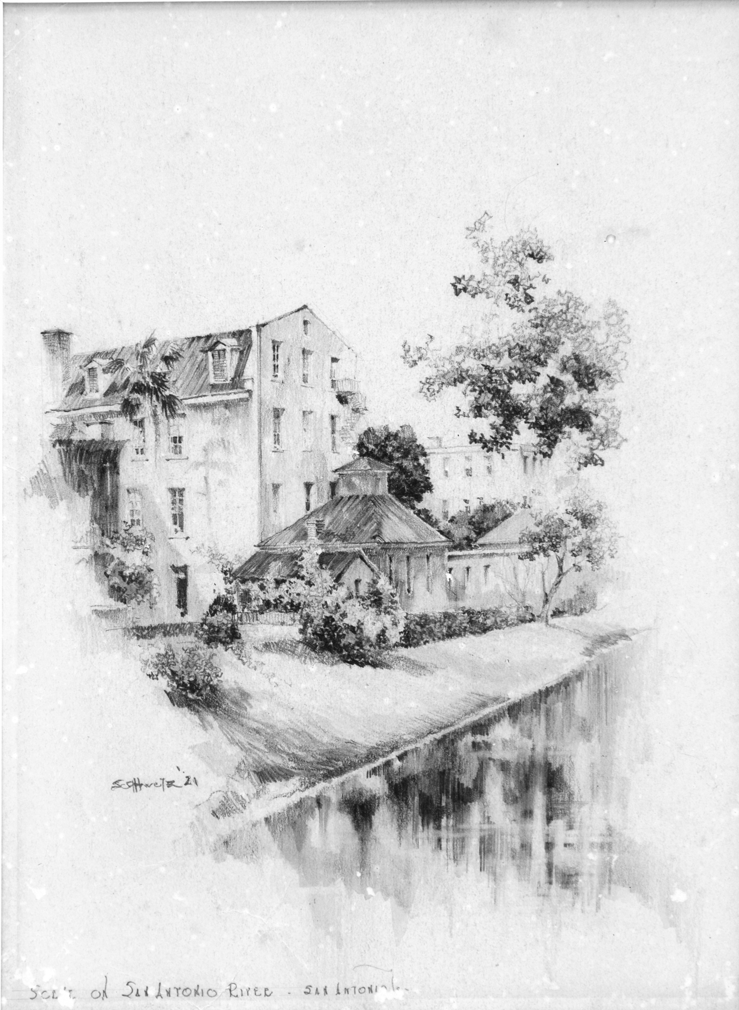

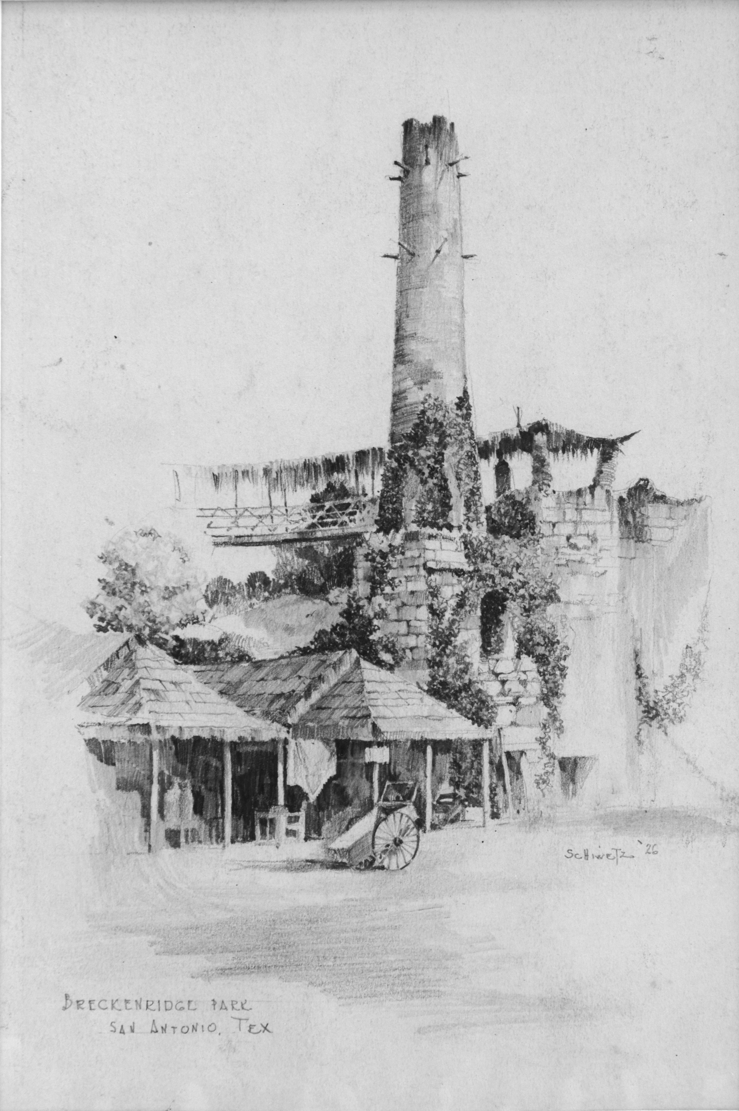

It was also at Thomson and Swaine that Schiwetz made his first overtures to the New York publication Pencil Points: A Journal for the Drafting Room, the prestigious architectural journal that the young delineator would later leverage as a major stepping-stone for his career. During his time at Thomson and Swaine, Schiwetz entered several of his drawings into the series of occasional contests sponsored by the journal. Correspondence reflects that Schiwetz submitted drawings to the Pencil Points competitions on at least nine occasions between March 30, 1926, and August 3, 1927, winning several cash-prize awards from the publication.17 The Bryan Eagle reported in July 1926 that Schiwetz’s sketch of Brackenridge Park in San Antonio would be published in the magazine’s May issue, making it his third publication in the prestigious journal by that time.18

In a letter to Schiwetz on August 11, 1926, apparently in reply to a previous note, Ralph Reinhold, publisher of Pencil Points, wrote to the young draftsman:

The very nice things you say about PENCIL POINTS are certainly appreciated. To try and please is one thing but to know that your efforts are really hitting the mark is most encouraging. And it is the sort of letters that you write that make us want to give the best that is in us. We are always glad to receive your interesting sketches and trust that you will continue to send them to us.19

In April 1927, Schiwetz received notice from Pencil Points that another sketch of his, Scene in Austin, Texas, would be published in the May issue of that year.20 Schiwetz remained at Thomson and Swaine for a little over two years, capitalizing on his experiences and contacts there to eventually move to Houston to try his hand as a freelance delineator in early 1927.

Throughout his trials to secure employment in Dallas, and especially after joining Thomson and Swaine, Schiwetz sought to augment his instruction at Texas A&M with continuing education in the arts. Aside from the applied apprenticeships that he cultivated on arrival in Dallas in 1922, there were very few fine arts training venues available to a full-time working professional such as Schiwetz. His arrival and stay in Dallas predated the dynamic arts scene that would shortly come to full blossom in the city in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Southern Methodist University (SMU), the city’s private university, had not yet begun its fine arts programming at the time of his arrival. The city’s two private art schools, run respectively by Vivian Aunspaugh (1869–1960) and Frank Reaugh (1860–1945), were too costly and too structured for a young artist like Schiwetz, who was trying desperately to forge a living in a fine art field.

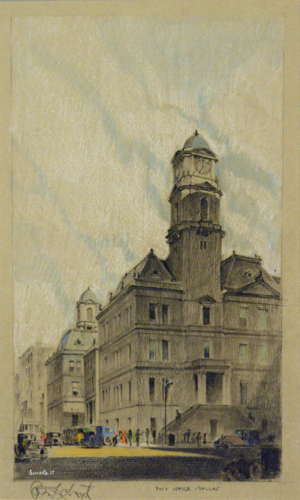

The Dallas Fine Arts Association was the city’s most prominent artists group at the time, having been founded by a group of eighty artist in 1903. With their assistance the city maintained the Dallas Public Gallery at the State Fairgrounds, the rudiments of which would later become the Dallas Museum of Art. The Fine Arts Association and Dallas Public Gallery were the centerpiece of the city’s art scene in the early 1920s and maintained an active exhibition schedule. Under the leadership of Sallie Griffis Meyer, the group presented popular, well-attended, annual exhibitions at the State Fair of Texas as well as grand art events attracting elite Dallas society at venues such as the Adolphus and Stoneleigh Hotels. As an interested newcomer, Schiwetz would have certainly been aware of the Dallas Fine Arts Association and likely availed himself of its exhibitions as a means of broadening his own education and exposure to the arts scene in his new “hometown.”

In 1925, about the time of his engagement with Thomson and Swaine, the Highland Park Society for the Arts was founded by Elizabeth Bailey. Under Bailey’s leadership, the society operated gallery space in the new Town Hall of Highland Park. Schiwetz’s drawings likely came to the attention of Bailey through his work with Thomson and Swaine’s Highland Park projects. Regardless, the influential Dallas art matron was sufficiently enamored by Schiwetz’s draftsmanship to grant him his very first solo exhibition at the Highland Park gallery in 1927.21

Schiwetz seems to have been especially active in the Dallas Architectural Club, which afforded networking opportunities, exhibitions, and informal professional development for its members. Schiwetz availed himself of the club’s informal classes, which stressed architectural drawing techniques. In 1925, his work was hung among those of fifteen Dallas architects at a club-sponsored art exhibition at the Norvell Galleries. The event was covered for the city’s newspaper by artist/architect Ralph Bryan (1892–1965), who described the significance of the exhibition as “unique in the annuls of local art . . . for there is assembled for the first time in history a showing of the work of Dallas architects.”22

Schiwetz likely first came in contact with David Williams (1890–1962) and his young colleague O’Neil Ford (1905–82) through his participation in the Dallas Architectural Club, both of whom were members of the association. Ford had come to Dallas in 1924 to apprentice with Williams, the father of regional architecture in Texas. The two men built a reputation for a style of indigenous architectural design. Ford rose to fame and prominence as a protégé of Williams, the duo becoming the most recognizable advocates of a distinctly unique Texas architecture.23 As a young architect active in the club’s offerings, Schiwetz would have been acquainted with Williams’s work on indigenous Texas design and likely affected by his philosophies in this regard. He certainly developed a relationship with Williams’s younger peer, Ford, the two being active participants in the club’s Sunday sketch classes.24 There Schiwetz and Ford formed a friendship that lasted through the remainder of their careers and, beginning in the 1950s, they worked closely on art and architectural preservation projects.

Ford was also an aspiring artist during his early career in Dallas and was at the epicenter of the development of an energetic art scene there in the late 1920s and 1930s. He and Williams acquired apartment space in an old house in the city’s Oak Lawn section. Dubbed the “Studio,” their office/abode became a gathering point for artists and intellectuals within the community. Through this circle, Ford became deeply connected to the group of emerging Regionalist painters who were establishing a bulwark in Dallas.25

Among the mutual friends shared by Ford and Schiwetz was Thomas Stell, who had been Schiwetz’s grade school classmate back in Cuero. Their post-high school years had many parallels, and their professional and artistic paths often crossed throughout their careers. Whereas Schiwetz had gone to Texas A&M from Cuero High School, Stell had completed his secondary education at a private military academy in San Antonio. From there, Stell matriculated at Rice Institute, briefly studying architecture. He moved to the Art Students League (ASL) in New York from 1923 to 1925 (three years before Schiwetz’s own ventures there) and then studied at the National Academy of Design until 1928 (briefly overlapping Schiwetz’s arrival in New York). Stell returned to Dallas in 1929 to join Olin Travis as instructor at the Art Institute of Dallas (AID), once again missing Schiwetz’s reported encounters at the institute by a couple of years. At the AID, Stell was an influential instructor of Dallas Regionalists, including Gerald (Jerry) Bywaters (1906–89), Everett Spruce (1908–2002),{ and William Lester (1910–91). Stell taught drawing at the Dallas Architectural Club in 1929 and also worked with architects David Williams and later O’Neil Ford on their surveys of indigenous architecture. In the mid-1930s, he became the state director of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Index of American Designand later served as an instructor at the University of Texas at Austin and Trinity University.26 Given their boyhood friendship, as well as their shared interests and common circle of colleagues in art, architecture, and preservation, Schiwetz and Stell maintained ongoing contacts throughout their careers, although the pair never seemed to have worked in tandem on their respective artistic endeavors.

It seems likely that Schiwetz may have first encountered Jerry Bywaters prior to his departure from Dallas in 1927, before both ended up at the ASL in 1928. Bywaters and O’Neil Ford were already acquainted by that time, and Schiwetz’s introduction to Bywaters may have occurred through this mutual connection. Bywaters was younger than Schiwetz and had graduated with a degree in comparative literature from SMU in 1926. While at SMU, Bywaters pursued art courses and had even served as art director for the Regionalist journal Southwest Review. As was Schiwetz, Bywaters was trying to overcome familial objections to a future in art. (However, unlike Schiwetz’s father, who demanded his son pursue engineering, Bywater’s father had apparently compromised his expectations to the degree that he merely encouraged his son to quell his art interests through a paying job in commercial art rather than as full-time painter.) Bywaters did convince his parents to allow him to attend the ASL to fulfill his art interests, and his brief term there in 1928 intersected the period when Buck matriculated at the institution. It seems likely that the young Texans extended their personal acquaintances there. Nonetheless, Bywaters returned to Texas in late 1928 to pursue his distinguished career in Dallas as an artist, critic, curator, and teacher.27

At some point after Buck returned to Houston in 1929, he and Jerry Bywaters assumed what was to become a long-standing professional relationship. Both shared a Regionalist aesthetic and an appreciation of fine printmaking. His biographer, Francine Carraro, explains that, by the early 1930s, Bywaters along with other Dallas contemporaries, became vocal and coherent in developing the idea of a regional expression and formulating an appropriate painting style. He welcomed Schiwetz into the fold.

Bywaters went on to serve as director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Art (DMFA) from 1943 to 1964, and from that post he would eventually provide Schiwetz three solo exhibitions at the DMFA. In the late 1940s, when describing Schiwetz’s progression and artistic output, Bywaters was quoted as:

M. Schiwetz is a Texas artist whose development has been influenced by a great diversity of professional interests. . . . [Schiwetz possesses] a severe discipline in observing the factual side of processes, industries, and particular sections of the region. He has made hundreds of careful pencil studies and many watercolors, drawings, and prints. His most recent paintings possess great vitality, rich plastic color, and intriguing subject matter. At all times this painter searches the cities, the landscape, and activities of the people for the character which gives individuality to a region, but beyond this is a new-found ability to give graphic power to his ideas.28

Another artist peer in Dallas who especially captured Schiwetz’s attention in those early years was Ruby Lee Sanders (1901–86), whom he met in early 1925. A talented and aspiring young artist herself, Ruby Lee worked as a sales director for DeVoe and Reynold, the city’s principal art supply depot of the period. With their shared passion for the arts, as well as each other, the couple developed a budding relationship and eventually married in February 1926.

Buck recounted that he and Ruby Lee attended art classes together at night. Although records are sketchy concerning the specific source of their shared training in Dallas, one possible institution that the couple may have occasionally visited for evening art forums is the AID. The institute was formed by Olin Travis (1888–1975) and his wife, Kathryne Hail Travis (1892–1972), in January 1926, one month before the Schiwetz’s marriage. A 1969 newspaper interview refers to Buck and Ruby Lee attending Travis’s academy together, describing their attendance at loosely organized evening activities at the new school.29 In announcing the opening of his art institute in Dallas, Travis opined that his school “would be incomplete without being in a position to provide instruction of the highest order in the various branches of illustration and advertising art.”30 Thus, Travis’s curriculum would certainly have had professional appeal to an aspiring commercial artist such as Schiwetz. While no known record of Buck’s or Ruby Lee’s formal enrollment at the AID has been found, the later news account seems plausible. The couple may well have attended informal artists’ gatherings or evening lectures there prior to their move to Houston.

Near their first anniversary in early 1927, Buck and Ruby Lee relocated to Houston. There, Buck freelanced his way as a delineator for some of the city’s most important architectural firms and as an independent advertising artist for some of Houston’s major business concerns. His architectural renderings of the time include work for John Staub (1892–1981), the foremost purveyor of country homes in the upscale Bayou Bend community and other exclusive enclaves about town.31 In addition, he did work for Joseph Finger (1887–1953), whose firm designed notable high-end residences such as the Boehm home, as well as helping shape Houston’s early skyline through designs of important public structures such as City Hall, Jefferson Davis Hospital, and the Hobby Airport Terminal.32

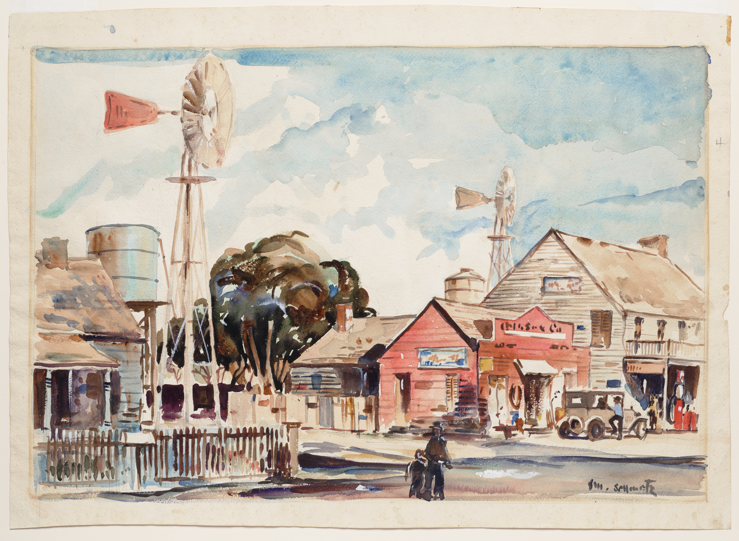

When not drawing for money, Buck also took advantage of Houston’s proximity for travel to San Antonio and Galveston, where he sketched the Texas coastline and the missions and experimented with watercolors.

In Houston, Buck collaborated with architect Vance Phenix (1897–1983) to design the plans for “Honeymoon Cottage.” The two submitted their drawings for a competition jointly sponsored by the Houston Architectural Club and the River Oaks Development Corporation. The young architects not only won both the five-hundred-dollar first prize and seventy-five-dollar third prize for the competition, but their winning plans also earned Schiwetz yet another publication in Pencil Points. In July 1928, the magazine provided a seven-page spread, “The Honeymoon Cottage Competition,” that included photographs of both Schiwetz and Phenix, as well as their winning entries. Their cottage design was subsequently constructed in the River Oaks subdivision.33

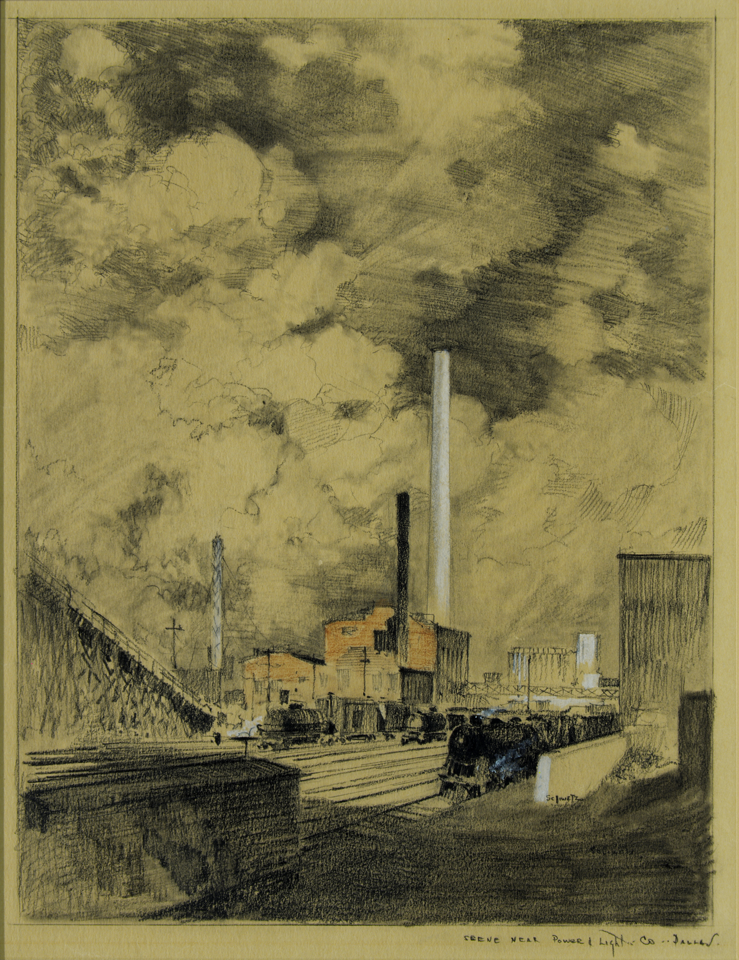

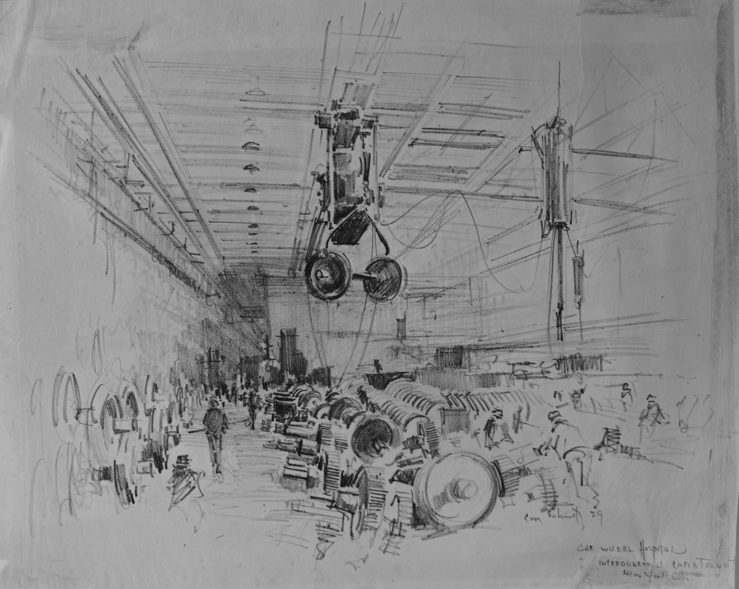

In 1927, Buck received an important commission from Anderson, Clayton and Company to create a series of ads for a giant promotional campaign titled Industry in Texas, to be published in Commerce and Fortune Magazine.34 The large cotton firm sought to memorialize the strength and diversity of the burgeoning Texas economy through a dedicated year-long advertising series. The Anderson, Clayton assignment was the artist’s most important job to date and served to introduce Schiwetz’s work to the Houston-based cotton firm, which would later prove a major benefactor in his career. He submitted fifty-two Texas drawings for Anderson, Clayton that were published in the company’s advertising tribute to their home state. The assignment garnered the young freelancer a substantial professional fee and a corporate bonus, but beyond that, it placed Schiwetz’s Texas imagery at the forefront of a major New York business publication every week for an entire year—a major accomplishment for a budding commercial artist.35

In that same year, Schiwetz also placed his first works into a juried exhibition at Houston’s new Museum of Fine Arts, entering a series of drawings in Exhibition by Houston Craftsmen, an effort that earned him honorable mention in the show.36

Texans on the Town: Art Adventures in New York City

With commercial opportunities now rising and his imagery displayed on the pages of significant national publications, Buck began to contemplate the possibilities of parlaying his Houston freelancing successes into further arts training and job prospects in America’s foremost art center, New York City. With Ruby Lee’s encouragement and with receipt of his Anderson, Clayton bonus, the young couple acquired a new automobile and embarked on a circuitous, cross-country sojourn in 1928 from Houston to New York City via Taos, New Mexico.

Why Schiwetz chose to go first to Taos is anybody’s guess. Perhaps the area’s cool mountain air offered the couple a pleasant spring respite from the humid coastal environs of Houston, or perhaps he wanted to become better acquainted with Taos painters who had established their popular art colony in the village. He certainly would have been familiar with the Taos founders from his days in Dallas, where the Highland Park Society of Fine Arts had sponsored exhibitions of the group during his time there. He may have also encountered their work on exhibition at the Witte Museum during his occasional travels to San Antonio. Nonetheless, the Schiweitzes departed Houston for Taos, arriving there in late spring. There he met Walter Ufer (1876–1936) and engaged in private instruction and critique with the national academician and former secretary of the Taos Society. His instructional output included renderings of architectural elements in the vicinity as well as sketches of Native American subjects around the Taos Pueblo.

He offered examples of these works for Ufer’s critique in a regimen that Schiwetz described as follows:

And we would go out to the Pueblos and draw, bring them to him and he would criticize them. So I would go by there in the mornings around 10:00. He had his wife there. She was a marvelous pianist and she would play and we would sit and drink wine and he would look at my paintings that I brought in and criticize them. Then one day he said, “Now you are going to New York. I am going to see to it that you go.”37

Buck and Ruby Lee apparently stayed in Taos for several months, during which time the couple also made the acquaintance of other artists within the colony, including W. Herbert Dunton, another artist holding the moniker of “Buck.”38 Seeking to move on to their ultimate destination of New York City and hoping to avoid the worst of New Mexico’s fall rains that tended to wash out roads and impair travel, the couple departed Taos in late September. As he left, Schiwetz carried with him letters of introduction and recommendation from Ufer to important associates in New York. Schiwetz later described these references only by the last names of Davis (likely Stuart Davis, who had summered in New Mexico in 1923 and was on the ASL faculty) and Hawthorne (likely national academician Charles Webster Hawthorne, with whom Buck’s friend Thomas Stell had previously studied at the league).39

After leaving Taos, Buck and Ruby Lee briefly looped back through Texas with a final stop in Dallas as a special guest for the Sunday Sketch Class of the Architectural Club, including O’Neil Ford and his former comrades in Dallas. On October 5, 1928, the Dallas Morning News reported on the sketch class:

Much interest will attend the excursion of Sunday, since E. M. Schiwetz, a Houston artist, will be the honor guest of the class. Mr. Schiwetz is in route to New York to continue his study of lithographs and etchings after an interesting summer with the artists of Taos, New Mexico where his work was warmly praised by men such as Walter Ufer and Herbert Dunton.40

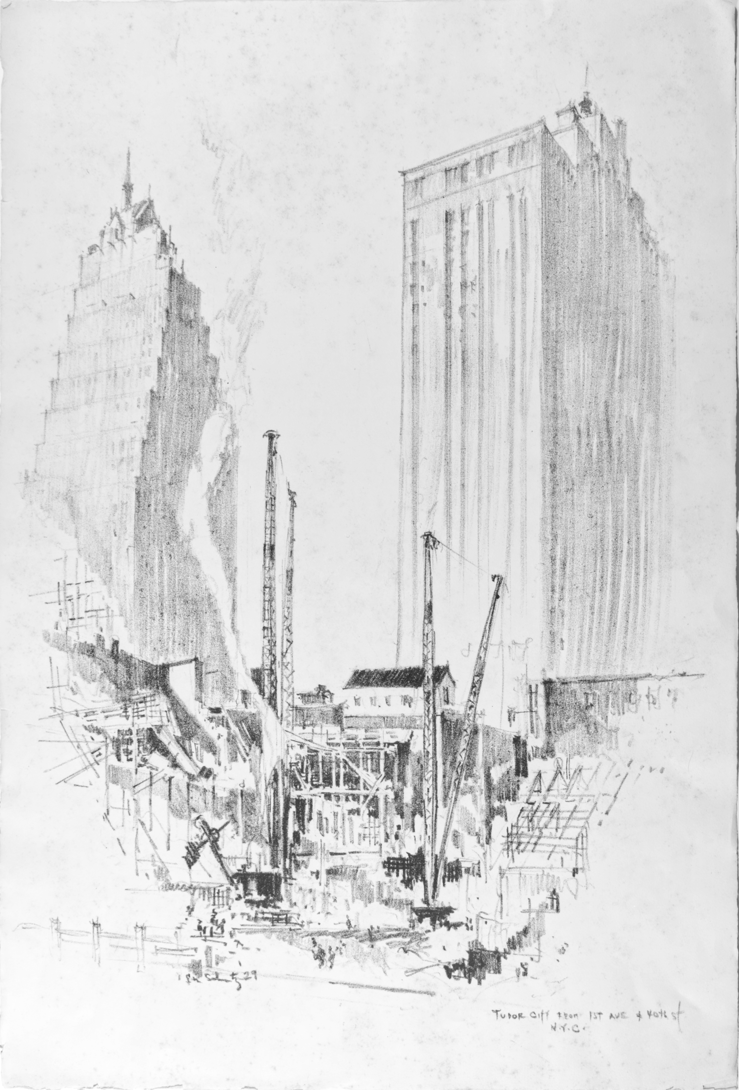

From Dallas, Buck and Ruby Lee then proceeded on to New York by auto, sketching at stops along the way. They reached the city in mid-October 1928, in time to locate a small domicile on 108th Street, an apartment having previously been the composing studio of Victor Herbert (1859–1924), and enroll for the fall session at the ASL) New York must have been an exhilarating adventure for the two young Texas artists. While they had little money, they seem to have fully embraced the city and its arts scene, immersing themselves in as many of its sights, sounds, and artistic resources as they could take in and capitalizing on their presence there to expand their respective skill sets and broaden their professional contacts.

Buck enrolled in an ASL evening course on lithography and etching taught by Eugene Savage (1883–1978). He saved his days for valuable sketch time, exploring the Brooklyn and Metropolitan Museums of Art and actively scavenging the city’s advertising and architectural firms in search of job prospects.

The exact genesis of Schiwetz’s interest in printmaking is unknown, although at first glance it seems a natural progression given his interest in drawing and proficiency as a draftsman. Printmaking had enjoyed renewed attention among many American artists beginning in the early twentieth century, especially after World War I. Schiwetz was likely introduced to etching and lithography at Texas A&M and was certainly inducted into the process during his time with Doctoroff and Cahoon in Dallas (both fine printmakers in their own right). He almost certainly would have encountered the etchings of Mary Bonner and L. O. Griffith, both of whom had solo print exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, during Buck’s time there. Certainly, as an aspiring commercial draftsman, Schiwetz would have appreciated the market potential of multiples produced from a single drawn image. Nonetheless, whether inspired by the lithographic process as a new mode of expression or transfixed by its commercial potential, Schiwetz pursued printmaking during his time in New York.

He complemented his studies with Savage at the ASL by working a couple of days each week as an apprentice at the print studios of George Miller (1894–1965), the country’s premier art lithographer, having established the city’s first print workshop for fine arts lithography in 1917. Miller had pulled prints for America’s foremost lithographers, including George Bellows, Thomas Harte Benton, Grant Woods, Howard Cook, and Stuart Davis.41 Coincidentally, Miller had also pulled prints for Buck Dunton, Schiwetz’s recent acquaintance at Taos, and it is possible that Dunton may have provided the young artist entrée to the Miller Studio. Through his work with Miller, Schiwetz was exposed to the best of American printmaking of the period and experimented with his own prints and etchings at the master’s workshop.

Meanwhile, Schiwetz sketched the city by day and made the rounds of innumerable ad and architectural agencies in search of work, eventually landing at the offices of Pencil Points. By the time of his arrival in New York in 1928, staff at the popular architectural journal would have almost certainly been familiar with Schiwetz’s work, having already extended him several cash prizes for winning entries in the journal’s open competitions and having recently published his award-winning house plans for the River Oaks “Honeymoon Cottage.” Nonetheless, Schiwetz recounted challenges in securing a productive audience for his work with editors there. When finally granted a review by Kenneth Reid (1894–1960), influential associate editor of Pencil Points, Schiwetz told of acting out the part of the stereotypical Texas cowhand, down to boots, hat, and serving a lunch of canned tamales, in an effort to break the ice with the publishing executive. Apparently amused by Schiwetz’s presentation, Reid was even more captivated by the artist’s portfolio, immediately recognizing the talent that lay within its pages and rushing the material to the attention of his editor in chief.42 The meeting with Pencil Points and Ken Reid proved providential for the young architect. Reid agreed to write a review of Schiwetz’s work for the journal, and in an article titled “A Sketcher from Texas: Notes on Some Drawings by Edward M. Schiwetz,” Reid introduced the artist to the journal’s national readership, including fifteen examples of Schiwetz’s work in the publication. In his article Reid concluded:

Were we given to moralizing, we might attempt to draw some conclusion from the career of this young draftsman so far as it has gone. We would point out that he formed a purpose even before he got out of school and then stuck to that purpose. We would point out that through working at the kind of work he wanted to do he has not only found pleasure in his work but has thrown all of his enthusiasm into it with the result that he is doing a good job. But let us forgo such preachments and accept the sketches for what they are—just good sketches made by a pleasant young fellow who is on the way to something bigger and better by and by.43

In addition to his article, Reid equipped Schiwetz with a list of personal references to several important commercial firms in the city, including arranging a meeting for the artist with principals of Eberhard Faber Pencil Company. The pencil company, in turn, commissioned Schiwetz to sketch a series of New York scenes utilizing Eberhard Faber products. Schiwetz quickly produced forty-two images for the company’s consideration. The firm selected an even dozen and incorporated five of these into a published brochure aptly titled The Artistic Possibilities of Black and Colored Lead Pencils Made by Eberhard Faber Pencil Company.44 Schiwetz was paid a sum of twelve hundred dollars for his efforts, one hundred dollars apiece for the drawings. This was his first major score on the New York scene, affording him and Ruby Lee an overdue financial lifeline to support their continued stay in the city. Soaking in every opportunity to expand his own knowledge, Buck once again leveraged time with Eberhard Faber to apprentice with several of the company’s established artists, observing and gleaning instruction from notable draftsmen such as Otto Eggers (1882–1964), Chester B. Price (1885–1962), and Hugh Ferriss (1889–1962).45 Other work assignments in publications such as Scribner’s and House Beautiful came his way, bolstered by the recommendations of his new acquaintance Ken Reid.

Beyond business introductions for the young artist, Reid used his influence with the New York Architectural League to arrange a solo exhibition of Schiwetz’s works cosponsored by the League. Staged apparently within gallery space associated with the publisher’s offices, Reid quickly organized a display of Schiwetz’s drawings and lithographs. The hasty installation apparently required other artists whose work was presently up in the space to remove theirs to make way for the Schiwetz materials. Among the artists who graciously made room to accommodate Schiwetz’s installation was William Spratling (1900–1967), then a professor of architecture at Tulane University in New Orleans and later internationally renowned as a pioneering silversmith and jewelry designer in the Mexican renaissance at Taxco.46 Spratling knew great pencil work when he saw it, as he had published his own treatise Pencil Drawing in 1923, and his article “The Expressive Pencil” was published in Pencil Points only four months after Schiwetz’s own write-up in the journal. Spratling’s article extolled the virtues of finished drawings as a fine art: “It has only been within the last decade that drawings done in pencil have come to be regarded as something complete in themselves and perhaps of real value as artistic expression for those men who did them.”47 Schiwetz described his own such finished drawings as “pencil paintings.” Apparently Spratling saw such value in Schiwetz’s compositions that he readily gave consent for Buck’s use of his exhibition space, telling Buck that he considered the gesture an “honor . . . and impressive thing for us.”48

Reid’s introduction, complemented by Schiwetz’s considerable talent and tenacity, enabled the young Texan’s work to receive ever more serious attention within the architectural and graphic art circles of New York. Evidence of Schiwetz’s growing stature came in the form of an offer to join the faculty at New York University as a drawing instructor. Schiwetz accepted the university appointment for the fall session.49 Thus, in the spring of 1929, Buck must have felt his New York ventures were paying off. He and Ruby Lee relished new friends, opportunities, and experiences in the city. They traveled upstate and to adjacent art centers on the Eastern Seaboard, sketching and meeting with artists along the way. The spring of 1929, however, also brought news of an even more compelling nature from back home in Texas.

An Entrepreneur of the Arts

While Buck had been cavorting about the country and making a name for himself in New York City, back home in Houston his close friend and former Aggie classmate Paul Franke, now an emerging star himself within Houston’s advertising ranks, had been formulating his own plans for showcasing Schiwetz’s graphic skills. Building on his advertising relationships with Anderson, Clayton, Franke envisioned a dynamic new ad agency for Houston, a partnership comprising himself as sales director, Joe Wilkerson as content manager, and Buck Schiwetz as art director, all done with silent financial backing from Anderson, Clayton. He pitched his ideas to Buck. In early May 1929 Schiwetz received Franke’s correspondence on a newly minted letterhead from the proposed firm of Franke, Wilkinson and Schiwetz formally soliciting Buck’s acceptance of the offer and requesting that the artist soon report to work at the company’s new office at the Cotton Exchange Building in Houston.50

With the headwinds of a looming depression beginning to dry up his New York assignments and the lure of more consistent work back home, Schiwetz accepted Franke’s partnership offer. He relinquished his pending faculty appointment at New York University and made arrangements for his return to Texas. Leaving in late May, Buck and Ruby Lee sketched their way through the South, finally reaching the Magnolia City in late July with “30 cents in their pockets.”51 As he settled into his role at his new ad agency during the waning months of 1929, Schiwetz watched as the stock markets of New York City plunged behind him, crashing America into the ominous Great Depression.

In retrospect, Schiwetz’s extended year in New York had served as a galvanizing experience for the young artist, validating his talent and appeal, expanding his professional experiences and contacts, and broadening his view and understanding of the art world. Returning home to Houston at age thirty-one, Schiwetz had already burnished his reputation as an adroit draftsman and accomplished printmaker with established New York credentials. More important perhaps, he left the city with his first major mentor and advocate, Kenneth Reid, with whom he continued to visit and counsel throughout the remainder of his career. In a letter to Norman Kent, editor of American Artist magazine, in 1961, Schiwetz wrote of his friendship with Reid and his importance to his career:

Yes, I shall never forget Ken Reid—my many visits with him in New York and Pleasantville. He gave me more encouragement and sound advice than anyone I have ever encountered in my search for a place in the realm of art and architecture. Rose and Ken were my guests in Texas—in Houston, in San Antonio, and in the Hills—and they delighted in it.”52 Kent replied:Ken Reid left a monument in his marvelous editing of Pencil Points and when he left its direction, something went out of the architectural magazine field that has never been replaced.53

Back in Houston, the Franke, Wilkinson and Schiwetz partnership evolved as yet another fortuitous opportunity for the artist’s career. While thrust again into a deadline-driven pace of artistic production, the agency’s backing by Anderson, Clayton gave Buck and Ruby Lee sound financial footing for the first time. They rented a house and studio in Houston and soon had a child on the way. Under Wilkinson and Franke, the firm attracted important new accounts across the Southwest, most notably the Humble Oil Company. With the backing of Texas’ most powerful oil and agricultural interests, Franke, Wilkinson and Schiwetz emerged as a major player in the Houston advertising sector. From his drawing table at the firm, Schiwetz leveraged the increased corporate exposure along with an ever-growing Rolodex of important contacts and clients as a means of simultaneously advancing his name and influence in the emergent Houston fine arts scene. He also used his agency assignments as a springboard for continued journeys across Texas and elsewhere in the interest of capturing imagery of his home state. He applied his weekends and holidays to return to explorations of the Texas coastline and there to perfect his continuing interest in the watercolor medium.

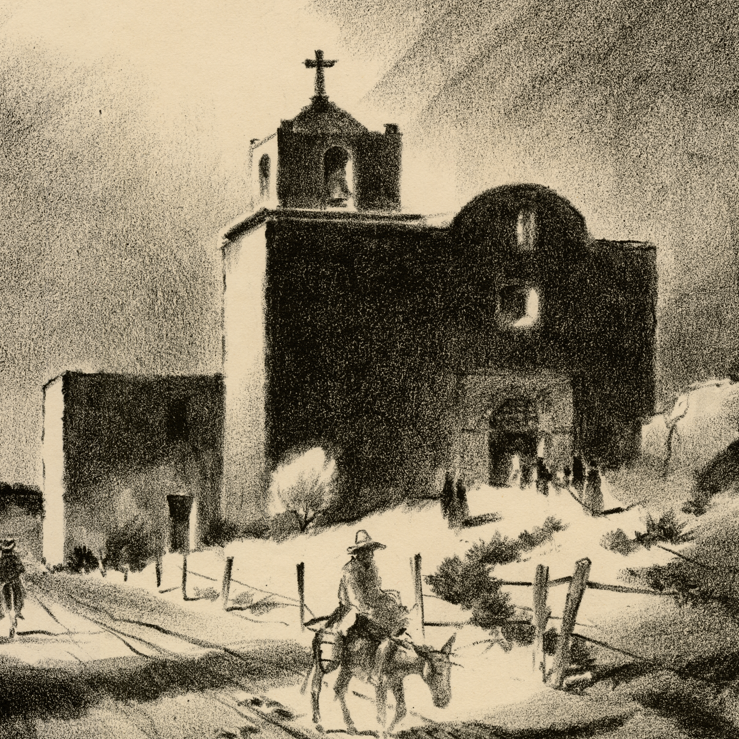

Beyond newfound responsibilities at the ad agency, Schiwetz continued making his own art and wasted little time in launching a vigorous exhibition schedule of his works in Houston and beyond. In 1930, he exhibited watercolors for the first time at both the American Watercolor Society in New York and the Philadelphia Watercolor Society, both venues likely facilitated by his friend Ken Reid. In that same year, Schiwetz entered a series of his lithographs in what would become the first of his twenty-two appearances at the Houston Annual Exhibition series hosted by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. His lithographs Manhattan Morning, Pecos Church, and La Bahia, Goliad, Texas received honorable-mention awards that year. His museum prize represented a remarkable accomplishment for an artist who had left Houston for the ASL to study lithography as a possibility and, upon his return three years later, garnered juried acknowledgment for his proficiency with the medium.

While it is not known whether these early lithographs were among those printed by George Miller, it seems plausible that they may have been, as Schiwetz is known to have produced lithographs at the Miller Studio during his internship there and later reported sending tracings back to Miller even after his return to Houston to be transferred for printing by the noted New York lithographer.54

In 1931, Schiwetz introduced his watercolors in the Houston Artists Annual for the first time, once again garnering honorable mention for his painting Early Morn at Mosquito Fleet, Galveston.

The emerging young artist had another banner year in 1932; he entered the Houston Artists Annual again, and his works were also juried into Southern States Art League and Texas Fine Arts Association exhibitions for the first time.

That same year, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, staged an exhibition titled Watercolors and Drawings of Edward M. Schiwetz, the artist’s first museum solo show. In addition, his watercolor entered at the Art Institute of Chicago’s International Watercolor Show, Early Morning at Pop’s Place, received a prize there. In 1933, three Schiwetz watercolors made their way into the Houston museum’s permanent collection via purchase awards at the Houston Artists Annual. He also had a solo exhibition at the Elisabet Ney Studio (now Museum) in Austin that year.

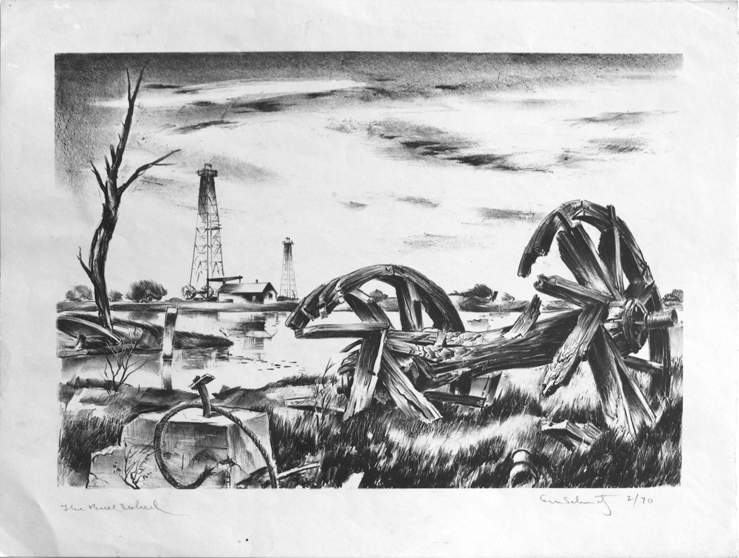

During the Texas centennial celebration in 1936, Schiwetz’s print Bull Wheel and Derricks was represented among lithographers at the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas.

He also won a prize in 1936 for his entry in the Art Association of New Orleans watercolor exhibition. The Witte Museum mounted a solo exhibition for Schiwetz in 1937, and, in 1938, he once again won prizes for juried works in the Art Association of New Orleans and Southern States Art League exhibitions.

While regularly submitting to such competitive and museum exhibitions, Schiwetz also cultivated local outlets for sale of his paintings. In 1930, he became a founding member of the new Houston Artists Gallery, an art cooperative incorporated by twenty-two of the city’s leading artists (nearly all female). In joining this group, Schiwetz showed his work among those of established Houston stalwarts such as Emma Richardson Cherry (1859–1954), Grace Spaulding John (1890–1972), Ola McNeill Davidson (1884–1976), and Ruth Pershing Uhler (1895–1967). The group maintained an active exhibition schedule throughout the mid-1930s, and Schiwetz was a consistent contributor to the gallery’s shows.55

Thus, a little over five years after his return to Houston, Schiwetz had already weaved his work solidly into the fabric of the Houston and broader American arts scenes despite ever-increasing obligations at a growing ad firm. He somehow managed to sustain an envious exhibition presence for the remainder of his career while at the same time churning out literary illustrations, the stream of which only served to further enhance his popularity among the general public.

Balancing Personal Expression amid Demand Production

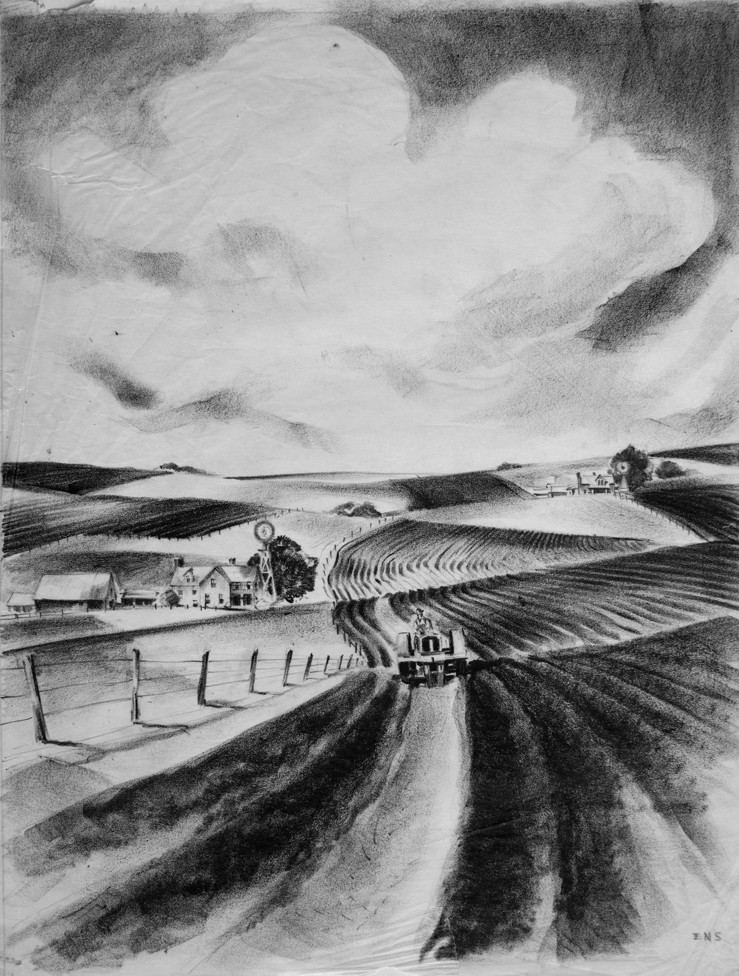

The 1940s pushed Schiwetz further as an artist. He began to seriously work in oils, perfecting this as a vital new medium in his growing arsenal. With the advent of the Texas General Exhibition series in 1940, Schiwetz seized on the opportunity to make this a new venue for additional museum exposure for his output, and his successes in these shows were soon punctuated by additional solo appearances and prize awards.

The annual Texas General exhibition series were a boon for Schiwetz as well as other Texas artists of the period. The exhibitions represented a cooperative endeavor by Texas’ leading museums to showcase the state’s growing share of art talent. The effort was led by Jerry Bywaters at the Dallas Museum of Fine Art (now Dallas Museum of Art); James Chillman (1891–1972) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Eleanor Onderdonk (1884–1964) at San Antonio’s Witte Museum. This core group, occasionally accompanied by other Texas museums, joined together to conduct an annual juried exhibition of Texas painters and sculptors, traveling their shows, along with accompanying catalogs, through a circuit of the major urban museums and offering an array of cash awards and purchase prizes for the artists involved. The series ran for twenty-three years, from 1940 to 1963, playing an important role in raising the profile of all Texas art and artists and serving as a catalyst for an ever-growing arts community at midcentury.

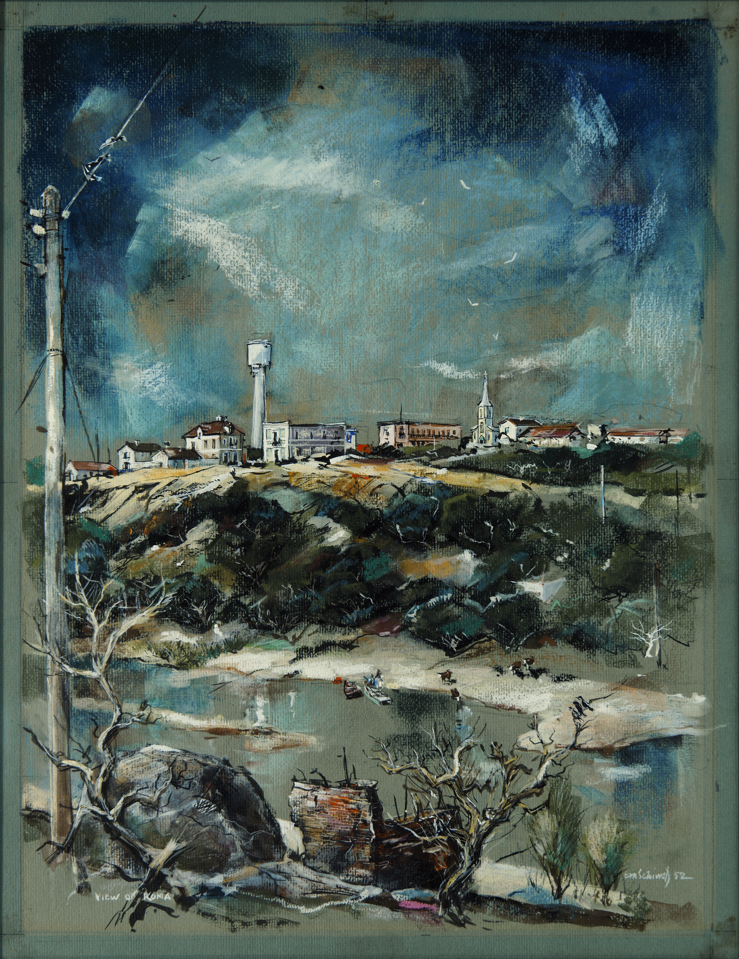

Beginning with the inaugural event in 1940, Buck Schiwetz showed seven times in the Texas Generals during the 1940s. He won prizes or citations in six of these exhibitions, including a 1944 award for his watercolor/mixed media La Cruz Rosado and two awards in his newest medium of oils—a purchase prize in 1947 for Sunday Afternoon—Eagle Passand an honorable mention in 1948 for the oil tempura View of Terlingua. At the eighth annual event in 1946, Schiwetz served with the jury to select the Humble Oil prize winner for that year.

In addition to the Texas Generals, Schiwetz remained an exhibitor in the Houston Annuals, his works receiving honorable mention six times during the 1940s.

He garnered the first of three solo exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Fine Art in 1946. In 1947, Schiwetz received two additional solo exhibitions at the Elisabet Ney Museum and Laguna Gloria Arts Center in Austin. He also had a two-man show with Otis Dozier in 1947 at the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Schiwetz continued to enter important out-of-state venues during the 1940s as well. His works graced gallery walls in Grand Rapids, Michigan (1940), in Tulsa at the Philbrook Museum (1940), in Chicago at the Art Institute’s International Watercolor Show (1943, 1944, 1945, and 1946), and at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center (1947).

Meanwhile, Schiwetz contributed more and more of his time and attention to organization building in support of Houston’s growing professional arts community. As the Houston Artists Gallery had declined in the late 1930s, Buck was at the forefront of establishing a successor organization similarly focused on expanding opportunities for sale of artists’ works as well as securing affordable studio and gallery space for the city’s artists. In 1940, he helped put together the Associated Artists of Houston. The group began with membership of seventy-five artists. Buck served as the founding president of the organization, working actively in support of member colleagues. While the new artists’ cooperative apparently experienced a relatively short lifespan, during Buck’s tenure the group was successful in securing a business manager for their operation, constructing a member-owned gallery, and securing studio space for member artists in a building on Pacific Avenue in the city’s Montrose area.56 In a 1976 interview, Houston painter and later gallerist Margaret Webb Dreyer (1911–76) described those early days:

And there was this big storefront across the road from us on Pacific Street. And Buck and Ruby Lee Schiwetz and my husband [Martin] and I took this place as our studio, and it had a lot of rooms upstairs. Then we rented to some other young artists, and there was just an artist group that worked out of this big, old storefront on Pacific. . . . We worked with Buck and Ruby Lee and Buck did so much for all the young artists. . . . Buck would round up all the paintings by all the young artists and take them over to the show [at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston], maybe several hours late, and James [Chillman] would wait there and everybody would have their things to be judged.57Later, in pursuit of yet other venues through which to show and promote more modernist modes within the Houston community, Schiwetz joined with Robert Preusser (1919–92), Alvin Romansky (1907–94), and others in 1948 to establish the Contemporary Arts Association, the forerunner of Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. The stated objective of the group was to “promote better understanding of contemporary arts . . . and their inter-relationships by means of exhibition and lectures so that the public will better understand and appreciate how these arts have a basis in and are an integral part of modern living.”58 Besides an inaugural exhibition, This Is Modern, notable for its survey of practical and expressive modern art forms, the first year of programming for the fledgling group also brought major exhibitions by such international icons as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Pablo Picasso, the latter show presented in association with New York’s Museum of Modern Art.59

Still later in 1948, Buck also became a founding member of the Houston Art League, lending his support to a vital community arts organization that still flourishes in the Houston arts scene. (Indeed, it was Art League Houston that would, some thirty-five years later, bestow its highest organizational tribute to Buck for his myriad lifetime achievements, naming him their first Texas Artist of the Year in a grand extravaganza in 1983.)60

Even as Schiwetz maintained his own active exhibition schedule and devoted himself to strengthening the hand of Houston’s art professionals, his day job at the ad agency was undergoing a major shift in the early 1940s. Two of the agency’s business partners, Paul Franke and Joe Wilkinson, were drafted into service in 1942, leaving Schiwetz as the only principal to manage the ongoing operations of what was now one of Houston’s largest and most significant advertising agencies. Schiwetz accepted the challenge of running the agency, balancing newfound executive responsibilities with continued art deadlines. Under his leadership, Schiwetz held the business together during these crucial years, and the firm even prospered with expanded accounts with Humble Oil and others. In the course of his new job, the transformed art director faced many new and unfamiliar duties, including managing Humble Oil’s broadcasts of Southwest Conference football, even serving as a “spotter” for legendary sportscaster Kern Tips (1904–67).61 Schiwetz endured his executive role, but it was a busy and stressful experience for him, and it became a tipping point for his growing dependence on alcohol. From that point on, he struggled off and on with alcoholism, more than once succumbing to institutionalization due to the disease. As World War II drew to an end and his business partners rejoined the firm, Schiwetz relished the return to his art duties.

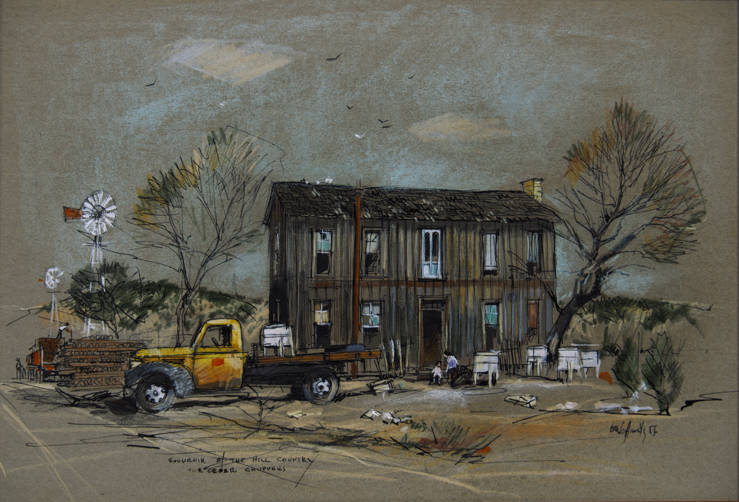

In 1945, Humble Oil Company approached Schiwetz with an unprecedented assignment, essentially giving the artist full rein in formulating illustrated stories of Texas subject matter for a new corporate periodical, the Humble Way. While the magazine still featured articles pertaining to the company’s oil-related business, its literary content was broadened with general-interest stories addressing the history, culture, and environment of communities wherein the company plied its practice. It represented an innovative concept at the time for corporate media, and it presented the perfect fit for Schiwetz. It gave the artist renewed permission to roam freely along the Texas backroads and explore again a countryside that he adored. The publication became a rousing success for Humble, and Schiwetz became a fixture in the popular magazine, his works appearing in sixty-seven issues between 1945 and 1963. His sketches reflected a diverse range of oil and historical subject matter.62

Yet even as he traveled the roads for his Humble Way assignments, Schiwetz remained interested in painting for himself. In 1946, he requested and received a brief sabbatical from the advertising firm to renew and collect himself after his arduous wartime management ordeal. He and Ruby Lee removed themselves to their small ten-acre retreat in Hunt, Texas, which they had acquired in 1935. Dubbed the “Half-S-Semi-Ranch” by the artists, it was a splendid lair situated on a knoll above a rushing waterfall on the Guadalupe River. Schiwetz later constructed a windowed, one-room studio, cantilevered above the falls on the river. He continued to paint in oils and increasingly experimented with abstract subject matter. In a 1955 article for the Texas Artist, Schiwetz declared:

I have always been classified as a “representational artist.” The realm of subject matter that I work in requires a fairly literal transcription of the scene. I try to deviate as much of an abstract pattern as I can when the occasion allows me to do so, and the client has a feeling for this particular approach. I find great enjoyment and satisfaction in observing an abstract or non-objective item of art when it is sound and honest. A beautiful piece of non-objective art gives me the same degree of satisfaction as a delightful musical composition.63

Schiwetz continued his forays into abstraction, but to his frustration and dismay, he found resistance to these nonobjective forms from dealers and patrons who clamored for his more signature style.64

Perfecting a Visual Blend of Texas History and Culture: Integrating Art, Illustration, and Preservation

During his time away in 1946, Schiwetz kept up his work for the Humble Way, and the company doubled down on his artistic production for their magazine in 1952, incorporating over fifty of his drawings with the writings of Frank Fields to produce The Texas Sketchbook: A Collection of Historical Stories from the Humble Way.

Humble Oil distributed the Sketchbook to its board of directors and issued copies widely to key clients, libraries, schools, and members of the Texas State Historical Association. Distribution was accompanied by significant news announcements by the company, and the booklet became acclaimed almost overnight, widely heralded as a huge success. The popular publication went through four more printings—including slightly revised versions in 1955, 1956, 1959, and again in 1962—and was later cited as one of the exceptional corporate publications to attain “collector status” in rare book and Texana markets.65 The Sketchbook also solidified Schiwetz’s growing reputation as a Regionalist chronicler of the Texas idiom and ushered in yet more opportunities for the artist to employ his hand at the interpretation of Texas history and myth through illustration.

With his historical assignments for the Humble Way, Schiwetz indulged in his early affinity for sketching old Texas buildings and landmark structures within the state, evincing his ever-growing interest in preserving them as artifacts of the state’s architectural and cultural heritage. In 1954, he joined a special architectural committee empaneled by the Texas Historical Commission, along with his friends Ima Hogg (1882–1975), Jerry Bywaters, and O’Neil Ford. He was on record in 1955 with his “hope to complete my itinerary of Texas in painting and drawing, chiefly its landscape and historic background in its old houses and communities.”66

Among those noticing the artist’s penchant for portraying the Texas scene was Frank Wardlaw (1903–89), director of the recently launched University of Texas Press and a respected and influential bookman. After his successful start-up of the University of South Carolina Press, he arrived in Austin in 1949 tasked with building a premier academic publishing house for the American Southwest. Capitalizing on the university’s ample faculty resources, including notables such as Walter Prescott Webb, J. Frank Dobie, and Roy Bedichek, Wardlaw was able to secure and publish a strong line on regional history, folklore, and nature studies. He also had a vision of regional art publications as a distinguishing centerpiece of his new brand, and he was no doubt attracted to Buck’s depictions of the Texas scene.

Inspired by successes of the Texas Sketchbook, Wardlaw first pitched the idea of a new publication featuring Schiwetz drawings in 1954. He envisioned the book as a large-scale, “coffee table”–style publication accompanied by an introductory essay and notes by the artist. The contract did not come to fruition until late 1955, but it eventually became Buck Schiwetz’ Texas, Wardlaw’s first major Texas art book.67 In taking this new book concept to his faculty advisory committee for approval, Wardlaw sought and received written endorsements for the project from Ima Hogg, James Chillman, Jerry Bywaters, and Eleanor Onderdonk.68 He also solicited and received substantial underwriting from Humble Oil Company. Buck Schiwetz’ Texas represented the first of five hardbound publications that Wardlaw would eventually publish by the artist, first at the University of Texas and later at Texas A&M University, where Wardlaw subsequently moved to start up what would be his third new academic press. Like Ken Reid before him, Frank Wardlaw became a major publishing advocate and lifelong compatriot of Buck Schiwetz, advancing his work and his reputation as the “Texas-most” artist of his time.

Wardlaw also introduced (actually, reintroduced) Schiwetz to the artist’s long-forgotten high school “professor” Walter Prescott Webb, who had actually instructed Schiwetz at Cuero High School long before his own high-profile tenure at the University of Texas. Reminding the stunned Schiwetz of their prior classroom encounters as student and teacher, Webb not only wrote the accompanying essay for the Schiwetz book, but he also nominated Schiwetz for a Guggenheim Fellowship to facilitate the artist’s completion of the project.69 (Regrettably for Buck, however, even with Webb’s endorsement, the Guggenheim fellowship never materialized.)

Wardlaw likewise introduced Buck to J. Frank Dobie, Roy Bedichek, and Tom Lea (1907–2001). Through the noted bookman’s introductions, Schiwetz quickly bonded within this distinguished intellectual fraternity, forging lasting friendships with these giants of Texas literature, albeit late in their lives. Webb invited Schiwetz to his Friday Mountain Ranch, and Dobie, in turn, had Schiwetz at his Paisano spread. Dobie had a great fondness for Schiwetz and his work. He asked the artist to paint his boyhood ranch home in Live Oak County on more than one occasion. Because of Dobie’s declining health, however, Schiwetz was never able to fulfill the writer’s commission.70 Schiwetz recounted a touching story of his last visit with Dobie at Paisano:

He had a beautiful ranch out there. Called it the Paisano. It had been raining like hell and them creeks was up. I didn’t realize it, but Barton Creek had risen. . . . Anyway we looked at it and I said “Well, that’s it.” He said “Aw hell! By Golly we’ll wade the thing.” He took his boots off and started off and waded across it. Well, we waded across. It was just about knee deep. Got across and got up to the house. He said, “What the hell, let’s cook us up some beans.” But first he got down some Black Daniels sour mash whiskey. He always drank in moderation. . . . We were about four hours out there. Beans were good too. . . . He said, “Tell you what we can do. Let’s go out and lay in the grass. I like to watch those buzzards. Like to watch ‘em fly.” We went out and laid on the grass and watched the birds. It was so inspiring. The wind, the currents. . . . So we just talked about things in general . . . about peach trees . . . had a little log cabin out there and I looked at it. . . . I spent the whole day with him out there. Yeah, we just laid right on the grass. And we discussed different things. . . . Discussed about Texas. . . .Last letter I got from him, tells the story about him getting sick. He had that trouble, but just wasn’t aware of it. He must have been cancerous. And he had that feeling. And that was a handwritten letter . . . the last one I ever got from him.71

With ties to Wardlaw, Dobie, and Webb along with his own acclaimed Sketchbook, Schiwetz moved further into literary illustration, publishing imagery in a string of popular Texas history publications in the late 1950s, including Reluctant Empire: The Mind of Texas (Fuermann, 1957), The Story of Texas (Bailey, Nesbeth and Gentry, 1957), and Interwoven: A Pioneer Chronicle (Reynolds, 1958).

Yet other book illustration projects followed in the 1960s and 1970s. Even during this period of immersion in Texas literary circles at midcentury, Schiwetz continued his advertising work at his company, which was once again undergoing major transitions. He also kept up his pace of museum exhibitions, as well as making time for his passion for legacy architecture.

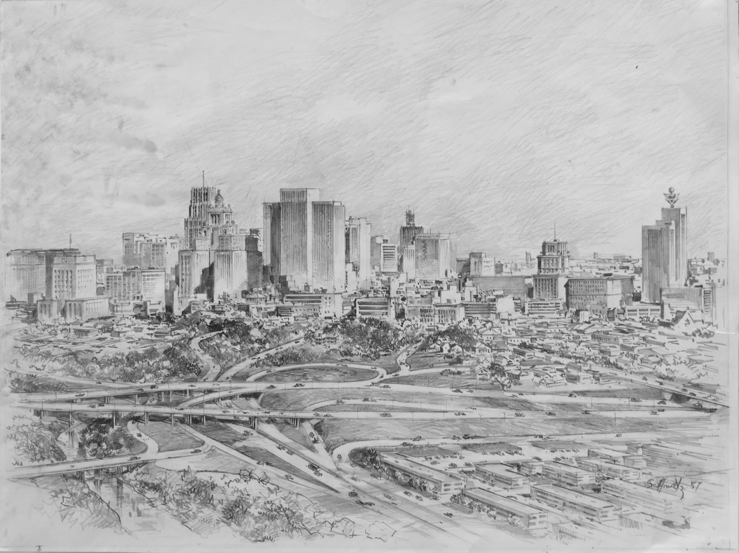

Throughout the 1950s, Schiwetz continued his appearances in the Houston Annuals as well as the cooperative Texas Generals. Under the curatorial eye of his friend Jerry Bywaters, Schiwetz was invited to serve as a jurist for the 21st Annual Exhibition of Dallas Painting, Sculpture and Photography in 1950. Later Bywaters awarded Schiwetz two more solo exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1951 and 1952. In 1952, Bywaters also included a Schiwetz lithographic image (along with one by Tom Stell) in the first portfolio of Texas printmakers, 12 in Texas, published under the auspices Southern Methodist University Press. As Bywaters began to formulate his notable series of survey exhibitions on important Texas artists, he included Schiwetz. Bywaters incorporated Schiwetz’s work in Survey of Painting in Texas in 1957, and in Texas art surveys of succeeding decades included him in A Century of Art and Life in Texas in 1961 and Texas Painting and Sculpture: The Twentieth Century in 1971.

Buck showed three times in New York during the early 1950s, exhibiting at Knoedler Gallery in Texas Contemporary Artists in 1952 and at the New York Watercolor Society in 1952 and 1954, winning a prize for his 1954 entry titled Souvenir of New Orleans. In 1952, his work was back again in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in a two-man show with Robert Preusser, the two men having only recently served as founding board members for the Contemporary Arts Association. The exhibition was titled Two Approaches in Painting. Preusser was the state’s foremost abstract pioneer, and though Schiwetz’s work was juxtaposed in the exhibition as the more representational alternative, the show actually foreshadowed Schiwetz’s own growing interest in nonobjective painting at the time.

In 1955, Schiwetz was selected for the prestigious D. D. Feldman Collection of Texas Art. His work, Frontier Oil Town, graced the catalog and traveled in the exhibition across the state to much fanfare. Surrounded by such growing fame, legendary gallerist Meredith Long (1928–2020) approached Schiwetz in the late 1950s to show his paintings in Long’s River Oaks establishment. It was a representational relationship that lasted, on and off, for the remainder of Schiwetz’s life. Long, who showed a grand range of artists and styles in his gallery, paired Schiwetz with sporting artists such as John Cowan (1920–2008) and Herb Booth (1972–2014) to great success.

Much had changed in Buck’s advertising career after the return of his partners from World War II. Buck, who had resumed his art director duties after a brief “retirement” in 1946, also held on to his football broadcast responsibilities and the Humble Way experiment as ongoing assignments. By 1949, Paul Franke had departed the company, and Kern Tips, Schiwetz’s announcer cohort, replaced him.72 The firm became Wilkinson, Schiwetz and Tips. In 1954, their business was acquired and merged with McCann-Erickson, one of the advertising world’s international mega-firms at the time (and a company still in operation today). After the company’s sale, Buck continued his role as art director for the new firm, but under the duress of his new assignment, he was soon overcome yet again by his drinking habit and admitted finally to the Starlight Sanitorium. After several months of rehabilitation there, he relented his director responsibilities, remaining active as an art consultant to the corporation and continuing his work with the important Humble Oil account. With his consultant schedule now more flexible, Schiwetz finally got down to finishing his work on Wardlaw’s book, and the completed publication hit Texas bookstores after great anticipation in early 1960.73

Books, Books, and More Books

When Buck Schiwetz’ Texas finally arrived at UT Press, Frank Wardlaw went to work. He supplied the promotional genius at his new press and launched the book to grand publicity. He sent review copies to book critics of all the major news outlets and arts journals, inviting their critiques, and made the amiable Schiwetz available for book talks and book signings at stores and boutiques across the state. The well-received publication emerged as a best seller, and reviews were carried in newspapers across the state. The publicity only added to the popular appeal that Schiwetz already enjoyed from his Texas Sketchbook and Humble Way days. Marshall Davidson (1907–89), the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s associate curator of the American Wing and director of museum publications, wrote his congratulations to the artist on receipt of his copy of the book and fondly recalled his experiences as guests of Buck and his brother, Berthold (Tex), in earlier times.74 Texan Margaret Cousins (1905–96), then managing editor of McCall’s Magazine in New York, wrote that the “engaging book and nostalgia brought me to the verge of tears when I was looking at it.”75 The book also caught the attention of Norman Kent (1903–72), editor of American Artist magazine, who published a lengthy and favorable review. In a letter to Schiwetz, Kent wrote:

My enthusiasm for your book has not abated after very careful study and I think that you have made an important contribution, not only to a record of Texas buildings, but in a broader sense to the whole field of Americana. I want to use examples of your book as fine propaganda for stimulating other artists to consider doing similar works in various sections of the country, though I admit that there are so few as ably equipped as yourself, with the exception of a limited number of architectural delineators such as deFonds, John Wenrich, Sam Chamberlain.Kent went further to proffer:

When the average architect attempts this kind of historical drawing the result lacks the painter-draughtsman approach; and when the average painter turns to this field his work lacks a solid foundation in this architectural form.76

The popularity of Schiwetz’s Texas led to yet another one-man exhibition at San Antonio’s McNay Institute in 1961. However, with his own health and that of his wife’s beginning to falter, Buck slowed his exhibition pace soon thereafter, choosing instead to consult for McCann-Erickson, paint for pleasure, and continue his experiments with abstractions. There would be an additional retrospective exhibition at the Institute of Texan Cultures in 1971, and he appeared in his last Bywaters survey exhibition that same year. But during the 1970s, as he approached his seventh decade, Buck essentially curtailed his long exhibition run.